[2nd chapter of this post (2/3)]

[Spanish version of this post]

In two previous parts of this post I tried to summarize the evolution of the Messinian salinity crisis, the period of widespread salt precipitation in the Mediterranean. This 3rd part focuses on our own research, aiming at finding a mechanism to explain the long first evaporitic phase (Stage 1).

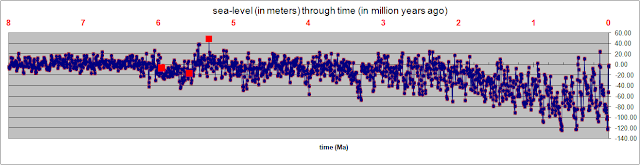

A key unknown that must be mentioned in advance is the depth of the last seaway that allowed the inflow of Atlantic water, the water that replaced the evaporation at the surface of the Mediterranean sea. Hydraulic calculations indicate that a too-shallow seaway (less than ~10 meters deep) would imply a reduction in Atlantic water supply and a drawdown of the Med's level (it would literally evaporate). In contrast, a seaway that was too deep (more than ~30 m) would allow too much mixing between both sides, contradicting the observed salt precipitation. Only intermediate values could allow uninterrupted salt precipitation during the first stage of the Messinian salinity crisis. But, how could the seaway keep in that narrow range of depths when global sea level changes are known to oscillate by several tens of meters? (See fig.3)

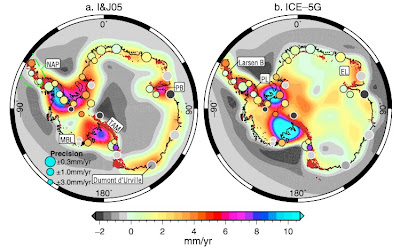

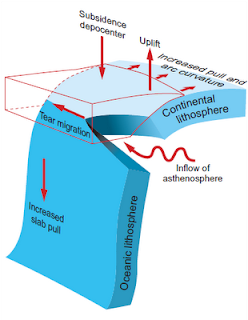

images obtained via seismic tomography of the Earth's mantle structure. These suggest that the uplift and shrinkage of the seaway may have taken place by a known geological process: due to the detachment of a dense piece of lithosphere (slab break-off). The tomographic images (see figure) use the arrival time of earthquake waves to derive the internal structure of the Earth, and show a lithospheric slab detaching from the Earth's crust underneath the Cordillera Bética. As this body sunk in the upper mantle, it would tear apart (slab tear) and trigger an isostatic rebound of the overlaying Earth's crust. This could explain the uplifted marine sediments in the Betic and Rif cordilleras, providing the uplift rates needed for the closure of the seaways.

But coming back to the essential problem of the mechanisms behind the salinity crisis: Tectonic processes as those discussed above are slow: to produce vertical motions of a few hundred meters they need at least hundreds of thousands of years. But sea level (see figure) changes by tens of meters in periods of a few thousand years. How could then the gateway remain in such a narrow depth range for more than 100,000 years? What kept the seaway neither too deep, nor too shallow in spite of the global sea level variations?

|

| 4. Cartoon illustrating the competition between the tectonic uplift of the seaway and its erosion due to the water flow feeding the Mediterranean (Garcia-Castellanos & Villaseñor, 2011). |

Our study (Garcia-Castellanos & Villaseñor, 2011) is based on relatively simple hydrodynamic calculations combined with erosion formulations that had been previously used for landscape modeling and river erosion studies. The results of combining these techniques to simulate the channel connecting the Mediterranean and the Atlantic show that the rate of erosion produced by the incoming waters that compensated the Mediterranean evaporation was similar to the tectonic uplift rate presumed for the Gibraltar Arc, suggesting that uplift and erosion may have been in equilibrium for a long period, keeping the connecting seaway at an approximately constant depth. The results also show that global sea level changes could also have been accommodated by erosion to some extent.

The model also predicts that this competition between uplift and erosion should normally occur out of phase, because the evaporation in the Med needs some hundreds or thousands of years to make the level fall. As a result, a cyclicity in terms of sea level and salt precipitation is predicted that could explain the intriguing cycles observed in the salt deposits all around the coast.

Global sea level fluctuations probably competed with the tectonic uplift by modulating the erosion rates exerted by the overtopping atlantic waters into the Mediterranean (see the supplementary information in the original publication).

Global sea level fluctuations probably competed with the tectonic uplift by modulating the erosion rates exerted by the overtopping atlantic waters into the Mediterranean (see the supplementary information in the original publication).

|

| Results from the model: 6. Equilibrium level of the Med as a function of the uplift of the seaway. |

- Stage 0 (before 5.96 million years BP). The Betic-Rifean island arc rose, shrinking the connections between Mediterranean and Atlantic.

- Stage 1 (5.96 Ma - ?). A last connection allows the inflow of Atlantic water, and erosion along this enters in competition with uplift, keeping the inflow roughly constant. The Mediterranean level descends some tens or hundreds of meters but it becomes quickly a saturated brine.

- Stage 2 (? - 5.33 Ma). Tectonic uplift exceeds seaway erosion and eventually disconnects the Mediterranean from Atlantic water supply. The Mediterranean goes dry, its level drops by 2 km.

- Stage 3 (5.33 Ma). The level of the Atlantic exceeds that of the Gibraltar land bridge and triggers a fast refill of the Med.

|

| 7. Cartoon of the simplest evolution suggested for the Messinian Salinity Crisis from the modeling results. Stage one corresponds to a cancellation of the outflow from the Med to the Atlantic; Stage 2 is the presumable desiccation starting when the threshold of the seaway becomes above sea level; The Zanclean flood is the refill triggered as the Atlantic waters found a way over the lowest sill of the Gibraltar ARc. |

The mechanism we propose for Stage 1 implies that the last corridor should undergo some hundred meters of erosion, carving a gorge while the surrounding mountains where rising. Finding this gorge nowadays won't be easy, since it has been probably overprinted by the landscape erosion taking place in the 6 million years passed since.

|

| 8. Salinidad actual de la superficie de los oceános. La mayor salinidad del Mediterráneo se debe a la mayor evaporación e insolación isolation de sus aguas. Source: World Ocean Atlas 2005 |

|

9. Artístic view of the surface and underground events during the early stages of the Mediterranean isolation.

Author: Manuel Mantero; licencia CC-BY-SA 3.0. |

References:

- Krijgsman, W., Hilgen, F., Raffi, I., Sierro, F., & Wilson, D. (1999). Chronology, causes and progression of the Messinian salinity crisis Nature, 400 (6745), 652-655 DOI: 10.1038/23231

- Duggen, S., Hoernle, K., van den Bogaard, P., Rüpke, L., & Phipps Morgan, J. (2003). Deep roots of the Messinian salinity crisis Nature, 422 (6932), 602-606 DOI: 10.1038/nature01553

- Garcia-Castellanos, D., Estrada, F., Jiménez-Munt, I., Gorini, C., Fernàndez, M., Vergés, J., & De Vicente, R. (2009). Catastrophic flood of the Mediterranean after the Messinian salinity crisis Nature, 462 (7274), 778-781 DOI: 10.1038/nature08555

- Garcia-Castellanos, D., Villaseñor, A. (2011). Messinian salinity crisis regulated by competing tectonics and erosion at the Gibraltar arc Nature, 480 (7377), 359-363 DOI: 10.1038/nature10651

- Govers, R. (2009). Choking the Mediterranean to dehydration: The Messinian salinity crisis Geology, 37 (2), 167-170 DOI: 10.1130/G25141A.1

- Garcia-Castellanos D, Villaseñor A (2011). Messinian salinity crisis regulated by competing tectonics and erosion at the Gibraltar arc. Nature, 480 (7377), 359-63 PMID: 22170684